Once again, it has been a while since my last post, due to Georgetown's finals and Christmas festivities, I have been extremely busy these last couple of weeks. But, to make up for the lack of posts since school started, I will be posting one post a day for the next week or so. These mainly consist of papers and lengthy emails I have made about movies, comic books, video games, etc.

This first post is a final paper from Fall of 2011, my first semester at Georgetown. For some reason, my class about the Post Modernist period in literature allowed us to write about anything from the period, not literature in particular. But, if I got the chance to write about Superman, I wasn't going to complain.

. . .

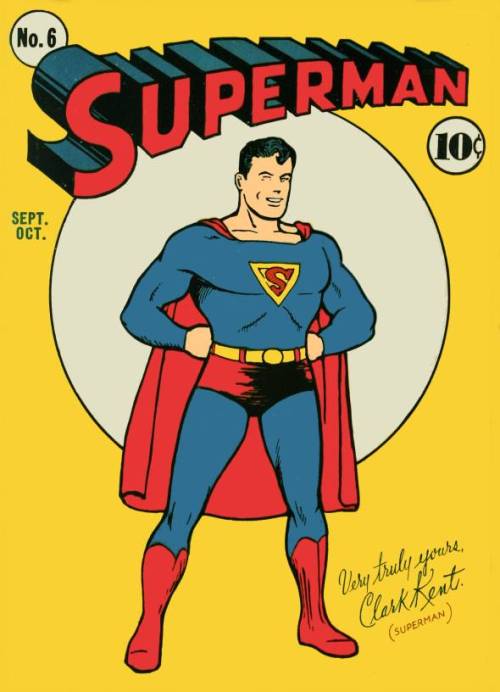

|

| I'm amazed Superman could fight crime with his eyes closed all the time. |

Harold

Donenfeld, the owner of the relatively new Detective

Comics publishing company, had no idea what to think of this startling

development. When he published the

“Superman” story in Action Comics #1 a

few months back in June 1938, he worried that the character would be too

fantastical for audiences to handle.

Thus, in the following four issues of the line, he kicked the

red-and-blue muscle man off the cover and returned to the safe and familiar

pulp stories that he knew people loved.

He felt fully confident that the character would merely fade into

obscurity, leaving him to one day scratch his head and wonder why he would ever

publish such a ridiculous tale. A man

from space, endowed with the powers of a god, lands on earth as a baby and

dedicates his life to fighting crime, while disguising himself as a

weak-willed, pathetic journalist; who would buy that? Who would believe it? According to a newsstand study that Donenfeld

requested, a lot of people would. In

fact, while other comic book titles only sold up to two hundred thousand comics

per issue, the Action Comics line repeatedly

sold over half a million copies (Bongco, 95)!

More fascinating, however, was the fact that despite Superman’s removal

from the cover, children continued to request “the comic ‘with Superman’”

rather than Action Comics (Bongco,

95). After the survey, Donenfeld decided

to put Superman back on the cover of Action Comics, trying to prove to himself

that it wasn’t a fluke, and watched each succeeding issue sell out.

|

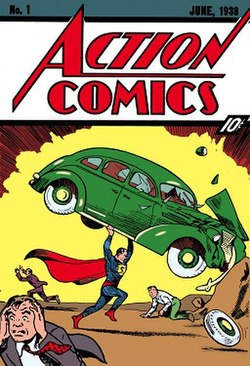

| Superman: Keeper of truth, justice, the American way, and smashing the fuck out of people's cars when they double park. |

His

mind was blown. Every notion that he,

and many other publishers, had conceived about the comic book industry had been

blown. To think that two introverted

teens from Cleveland had somehow created the perfect comic book character

astounded him, as did the idea that the two had failed to sell their idea for

years with no luck because editors had the same line of thinking as he did. Amazingly, by taking this chance to publish

the story that no one else would, Donenfeld had stumbled onto a cultural and

financial gold mine. Soon, Superman would

have his own radio show and become a staple of American culture. Even in the mere months after Superman’s

monumental success, dozens of imitators would begin to pop up out of the

blue. Men in capes and masks fighting

crime, including bizarre creations like the “Bat-Man” and “Captain

Marvel.” No one, not even the Man of

Steel’s creators, really knew how it happened.

To everyone, it seemed like unexplainable luck. Yet, given the factors behind his creation, such

as his appeal to the children and adolescents that eventually became his main

reader base and the time in history he was published, Superman was, in many

ways, destined to succeed.

Take

the influences and early lives of Superman’s two creators, Jerome “Jerry” Siegel

and Joseph “Joe” Shuster, whose age was a huge factor in Superman’s

appeal. When they developed the concept

of Superman, Siegel and Shuster were the same age as the children and

adolescents who became the Man of Steel’s biggest fans. The two Cleveland boys knew their own

personal interests and emotional struggles and knew to tap into these interests

and emotions to make Superman appeal to themselves, and thus any potential

readers of their own age group. In other

words, they wrote Superman as much for themselves as they did for anyone

else. For example, Siegel himself noted

that Superman rose from his “own personal

frustrations,” which were

quite prominent and overbearing due to the fact that Siegel was an introverted

bookworm who was bullied by his classmates and completely ignored by the

beautiful girls he adored from afar (Siegel, “Happy Birthday, Superman!”). Perhaps, he thought, he could finally get the

respect and attention for which he constantly yearned if he “could run faster than a train, lift great weights easily, and leap over

skyscrapers in a single bound”

(Siegel). Thus, when creating Superman,

he knew that he wanted to create two sides to the Man of Steel in order to

obtain his personal wish fulfillment (Siegel).

He knew that Superman’s alter ego, Clark Kent, would have to be a

stuttering, pathetic mess of a man that perfectly mirrored the inhibited,

intellectual appearance of Siegel and his friend Shuster (Siegel). Indeed, the bespectacled Kent possessed many

of his creators’ traits, from his ineffectual wooing of the tough and

independent Lois Lane to his timid and cowardly nature. In fact, even Kent’s reporter position was

similar to Siegel, who was a constant contributor to his school paper (Siegel).

| Siegel (Left) and Shuster (Right) |

Yet,

as everyone knows, Kent’s timorous behavior is just a front. With a removal of his glasses, Kent becomes

Superman, “a physical marvel, a mental wonder…destined to reshape the destiny

of the world” (Siegel and Shuster, 13)! Clark

Kent may be just a face in a crowd, someone who is overlooked or even shunned

by all his peers, but by a simple costume change, he becomes the person

everyone adores! Yet there is more to

this transformation than just the drama it provides. When writing,

Clark Kent personifies fairly typically the average reader who is harassed by complexes and despised by his fellow men; through an obvious process of self-identification, any accountant in any American city secretly feeds the hope that one day, from the slough of his actual personality, a superman can spring forth who is capable of redeeming years of mediocre existence. (Umberto and Chilton, “The Myth of Superman,” 15)

Umberto and

Chilton point out exactly what makes the dichotomy of Superman and Clark Kent

so appealing: adored by women and feared by the bullies of the modern world,

Superman is not only the epitome of Siegel and Shuster’s desires, but of the

desires of many young children and adolescents who experienced the same

self-consciousness and feelings of isolation as Siegel and Shuster did, and this

desire to be noticed, adored, and respected by one’s peers despite one’s

physical and social inadequacy is what makes Superman such an engaging and

inspirational hero.

|

| He's also one hell of a dancer. |

Yet,

as appealing as such a simple transition sounds, this dichotomy would not have

been as influential if Superman’s grand adventures did not perfectly reflect

the culture and/or respond to the emotions of the late 1930’s. While Superman’s dichotomy and simple

transition from unknown to idol would have probably appealed to most people at

any time, it was especially potent during the 1930s, a time when society was

becoming more mechanized, and men desperately tried to cling onto their

individuality in spite of society’s trend of forcing them to feel like numbers and

statistics (Umberto and Chilton, 14). The general public needed to find someone that

was above the trivial pressures of modern life, like the failing economy and

the increasing mechanization of labor, and Superman became that person. He stood above the skyscrapers and machinery

and became almost a mythological figure.

|

| Superman's going to give Adolf a stern talking to. |

Furthermore,

by reflecting the culture trends and media of the 1930s, Superman was a modern

and present hero, and was much easier to explain and understand than most future

based comics, like Flash Gordon. Throughout

Superman’s romp in Action Comics #1,

the dialogue was rich with slang, such as “seeing pink elephants” as a

reference to inebriation (Siegel and Shuster, 10). As mentioned before, Kent’s romantic

interest, Lois Lane, was a strong, independent woman and a fellow reporter

rather than a repressed and obedient housewife.

The art in particular was heavily influenced by pulp art that was

popular in comic books at the time, with Superman looking more like a bruiser than

his more graceful modern depictions, and his costume was influenced by the

artwork of muscle-building magazines, which Shuster frequently purchased and

were quite popular at the time (Benton, 12).

Even the name Clark Kent was influenced by actors Clark Gable and Kent

Taylor, and the concept of a man from space with superhuman powers coming to

modern society was borrowed heavily from Phillip Wylie’s 1930 novel Gladiator! Furthermore, the bulk of Action Comics #1, from the ads to the stories, appealed to children

of the 1930’s, and included cartoons of famous baseball players like Lou

Gehrig, and caricatures of famous actors.

From cover to cover, Action Comics

#1, and its famous creation, was the 1930s.

But

more important is Superman’s struggle against social problems that were

prevalent during this time. As mentioned,

Siegel noted that Superman was a vent for his frustrations, but it was not only

bullies that bothered him. With a

looming World War, a Great Depression, and even a greater awareness to political

corruption due to more advanced journalism, children back in 1938 lived in an era

of immense fear and anxiety. Thus, in

his grand adventures, Superman tackled these problems. Specifically in Action Comics #1, Superman confronts a well-known lobbyist who was

supporting a mysterious Congressional bill that would have forced the US into

the conflict in Europe. By carrying the

lobbyist away to jail (or for more information; the issue ends a dramatic

cliffhanger) Superman was doing his part to cut down on corruption (Siegel and

Shuster, 11 - 13). What is interesting

about this moment is not only that Superman takes such action, but also the depictions

of the ratty faced, conniving lobbyist and the abnormally plump fat cat

Congressman he meets with, making it somewhat obvious that two creators were pointing

out the people they felt responsible for rampant corruption in government and

portraying them in an unflattering way (Siegel and Shuster, 10).

But

what is so special about attacking these modern social problems? Wasn’t the aforementioned fact that he was

above all of this corruption and social pressures enough for readers? Not at all.

First of all, confronting such problems is what forms the basis of

Superman’s appeal: rather than being a ordinary man in an extraordinary place

and time, like his predecessors Flash Gordon and John Carter of Mars, Superman

was an extraordinary man in a ordinary time and place (Benton, 13). Unlike those men of pure fantasy, Superman

would be doing all he could to attack problems that kids really felt should be

fixed in their lives. This is clearly

seen in another segment of the story, where Superman fights and defeats a man

who had been beating his wife and reprimands the man as he landed each blow. Is that not what any child in a house of

domestic abuse, or even a friend of such a child, would love to do? By taking such action against crimes that have

been seemingly ignored by adults, children may see Superman’s fantastical

actions as achieving things that adults never could, and the comics provide “an

indictment against…older folk who have not succeeded in lessening crime

perceptibly or in seeing that justice prevails” (McCarthy and Smith, “The Much

Discussed Comics,” 100). Also, due to

the enormous stresses of the time, Superman’s adventures provided a much-needed

escape from the disasters that children felt they had no control over. One child, when asked why he liked reading

comics, noted that the bright and colorful pages of his favorite comic book

“took [his] mind off the war news for a while,” showing that comics were more

appealing to children than ever during a time of constant bad news (Strang,

“Why Children Read the Comics,” 339).

There

are many other reasons children adored Superman’s adventures, however. When asked by Dr. Ruth Strang of Columbia

University, children provided a variety of responses for their love of comics, thus

hinting at why Superman, and the comic book medium in general, appealed to

children and adolescents. It was not

only the desire to, as Strang describes it, fulfill their need to “overcom[e],

in imagination, some of the limitations of their age and ability for obligating

a sense of adventure denied to them in real life” or the release “from feelings

of inadequacy and insecurity and fear from aggression toward or from others” as

we have described before (Strang “Why Children Read the Comics”, 336). Some children just read them for relaxation or

for mental catharsis from the work of school.

Or, due to the mixture of art and short, yet still descriptive,

sentences, some children used them to learn to read, or even to supplement their

diction with new vocabulary that could be easily explained by the art provided

in the comic’s panels. This mixture also

made reading comics simpler than reading a novel in general, requiring less

thinking and strain than what was constantly required at school. Yet, Superman was quite proficient in two

comic book conventions that drew readers back to his comics week after

week. The first can be properly

described by a high school boy:

Comic strips appeal to the average reader like myself by three little words, “To be continued.” In almost every case before Superman puts in appearance, Lois, the leading lady of this strip, is ready to lose her life. Just when death is about to strike, “To be continued” pops up, and the reader anxiously waits for the next issue in order to see how Superman pulls Lois out of this one. These adventures go on forever. (Strang, 340)

In other words, by

leaving the reader in suspense of what is going to happen next (like Action Comics #1 did), Superman not only

makes the reader care about his adventures and even his supporting characters,

he makes the constant saving of Lois or the constant battling of evil never

lose its luster, even if it is a situation a reader has encountered many times

before. By leaving those three words, a

reader’s imagination takes off, letting them wonder what could possibly happen

next. The temptation and excitement to

see if what they have predicted comes true is too alluring to resist, and

Superman continues to draw their interest.

|

| WHAT DOES IT MEAN? |

The second trait provides the answer

as to why Superman’s adventures never seemed too silly or fantastical to

readers, as Donenfeld and other editors expected. One reader mentioned that while she did

realize Superman’s actions were indeed impossible, Siegel’s skillful writing

and Shuster’s impressively realistic art presented the Man of Steel in such a

way that gave the reader a feeling that “it is not fiction but really fact”

(Strang, 338). Indeed, Siegel and

Shuster did their best to see that Superman’s romps never become too

fantastical, such as the fact that Superman was not able to fly until 1943,

well after he was an established character (Booker, 614). Even in Action

Comics #1, Siegel does his best to explain Superman’s powers in ways

children can comprehend. After

describing how the residents of Superman’s home planet achieve super abilities when

reaching maturity, the narrator answers the reader’s disbelief with a jubilant

“Incredible? NO! For even today on our world exist creatures

with super-strength!” before providing the examples of the “lowly ant” that

“can support weights hundreds of times its own,” and the grasshopper, that can

leap “what to man would be the space of several city blocks” (Siegel and

Shuster, 1). By imposing examples a

reader can comprehend and have most likely already learned in schools, and then

imposing them onto a man, Superman’s actions become comprehendible and not

beyond the limitations of imagination.

There were, of course, other reasons

Superman and the idea of the superhero was not an extreme departure from the

norm as many editors believed. From

cinema to plays to classic novels, Superman has had many predecessors that, when

recognized, made Superman’s arrival seem more like a grand progression rather

than a complete departure. Beginning in

the era before comic books, which author Peter Coogan describes as the

“Antediluvian Age,” there have been dozens of men with superpowers, who fought

crime and maintained a secret identity, or have gone on grand and fantastical

adventures; Superman was merely the first to combine all of these ideas in a

pretty red and blue package (Coogan, 127). In particular, Coogan lists three categories

of adventure heroes that Superman eventually encapsulated and even defied: the

science-fiction superman, the dual-identity vigilante, and the pulp übermensch

(Coogan, 126). The first category included

beings like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

and H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man,

and was often defined by a character that is somehow more evolutionary advanced

than those surrounding him. Superman

defied this concept, however, for while the usual character was often tragic, considered

an outcast, and eventually grew to look down upon his supposed inferiors,

losing whatever humanity that remained, Superman remains completely supportive

of his adoptive planet and its inhabitants, and, in turn, most of the planets

residents support him.

|

| Just one of many results for a "Frankenstein Superman" Google Search. |

The

“Dual-Identity Vigilante” has been around since the times of Robin Hood, but

regained popularity with Baroness Orczy’s The

Scarlet Pimpernel (1903), which featured a French aristocrat dressing up as

The Scarlet Pimpernel in order to save other aristocrats from the guillotine in

revolutionary France. Like Superman, the

Pimpernel also had a pathetic alter ego, Sir Percy Lord Blakeney, whose “wimpy

playboy secret identity…contrasted with the stronger hero identity” (Coogan,

156). Superman defied this definition as

well, for Clark Kent was even more of a nobody than Sir Percy, making him so

superbly average it appealed to children in a time of lesser individuality. Also, while the masked avengers of this

convention were considered criminals for their illegal behavior, Superman fights

all crime, respects the laws of the land, and is loved by most of the police

and the government (with, of course, some more modern notable exceptions)

(Coogan, 154).

|

| It's because nobody cares about you, Clark. |

Finally,

the pulp übermensch included men like Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan (1912) and the character Doc Savage, both of whom influenced young

Siegel and Shuster. Yet, while these

characters were often called “supermen,” in was more in the vein of a

“physically and mentally superior individual who acts according to his own will

without regard for the legal strictures that represent the morality of society”

(Coogan, 162 – 163). Superman, of

course, would never go against the wishes of society, and in many ways, he

defines them. Yet, despite this contradictions, Superman stills owes his

origins and success to these characters, for, as Coogan notes “by the time of

Superman’s creation, these conventions so suffused pulp fiction that their

presence in the color-costumed adventures of superheroes would go unquestioned”

by readers (Coogan, 157).

|

| That's not to say he hasn't done stupid shit in his 70+ years of comic history. |

But Coogan also notes that while

Superman may not be the first superhero – mentioning characters like Popeye,

Hugo Danner from the book Gladiator,

and even another character by Siegel and Shuster known as Dr. Occult, who even

featured a similar color scheme to the Man of Steel – the Last Son of Krypton

was the first character to “fully embody the definition of the superhero and

prompt the imitation and repetition necessary for the emergence of a genre”

(Coogan, 175). And he did so by

presenting the three features of every Superhero that followed in his footsteps

– mission, powers, and identity – all in the first page of Action Comics #1. After

discovering his fantastical powers,

including running faster than a train and deflecting bullets off his skin, a

young Clark Kent states his mission,

dedicating his life to using these powers “into channels that would benefit

mankind” and, at the bottom of the page, he stands triumphant in the his famous

costume, thus presenting his identity (Coogan,

175). And while some other characters

may have had these concepts before, Superman was both the first to combine them

and to, as Dr. Randy Duncan and Dr. Matthew J. Smith note, redefine these

concepts that fit his hero personality.

In particular, the two point out that Superman’s mission is completely pro-social

rather than self-serving, so he is not fighting criminals for his own desires

and drives or out of vengeance, he is doing so to solely benefit society. And when it comes to identity, Duncan and

Smith note that Superman’s mission and powers are perfectly represented in his

image. Not only do the bright colors of

his costume reflect the fantastical nature of his powers and deeds, the famous

“S” on the Man of Steel’s chest becomes what the two define as a “symbol signs”

– “an arbitrary pattern…that reference an idea or thing” – of both his mission

and his desire to help others. (Duncan and Smith, 320). That is why the colorful picture of a man

lifting a car above his head while wearing blue and red tights did not confuse

the reader or dissuade them from buying the comic as Donenfeld expected. More likely, it fueled interest!

This is just a sampling of why

Superman was so influential and destined to succeed. The culture Siegel and Shuster were raised

in, their interests, their early lives, and even the books they read, all came

together to form a new, yet not radically different, character that perfectly

represented both the ways of American culture and the wish fulfillment of young

children and teens living in Depression-era America. Yet, as Duncan and Smith point out, superheroes

were not only tales that inspired wish fulfillment, they became an “optimistic

statement about the future and an act of defiance in the face of adversity”

(Duncan and Smith, 243). Superman was

not only the hero everyone wanted to be, he was hope in a time of poverty and

looming war. He came when America needed

him most, just as he always does in the comics.

Thus, it is no wonder why something so powerful, so fascinating, and so comforting

would sell prolifically, and become the definer of the American culture.

|

| God DAMN, my patriotism is so rock hard right now. |

Works Cited

- Siegel, Jerome, and Joe Shuster. "Superman." Comic strip. Action Comics #1 June 1938: 1-13. American Studies @ The University of Virginia, Dec. 2000. Web. 12 Nov. 2011. <http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ug02/yeung/actioncomics/cover.html>.

- Benton, Mike. Superhero Comics of the Golden Age: the Illustrated History. Vol. 4. Dallas, TX: Taylor, 1992. Print. The Taylor History of Comics.

- Coogan, Peter M., and Dennis O'Neil. Superhero: the Secret Origin of a Genre. Austin, TX: MonkeyBrain, 2006. Print.

- Duncan, Randy, and Matthew J. Smith. The Power of Comics: History, Form and Culture. London: Continuum International Pub. Group, 2009. Print.

- Siegel, Jerry. "Happy Anniversary, Superman!" June, 1983. Superman.nu. Fortress of Solitude Super Network, 2008. Web. 12 Nov. 2011. <http://superman.nu/a/siegel.php>.

- Strang, Ruth. "Why Children Read the Comics." The Elementary School Journal 43.6 (1943): 336-42. JSTOR. Web. 16 Nov. 2011. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/997772>.

- McCarthy, M. Katharine, and Marion W. Smith. "The Much Discussed Comics." The Elementary School Journal 44.2 (1943): 97. JSTOR. ITHAKA. Web. 12 Nov. 2011. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/997572>.

- Eco, Umberto, and Natalie Chilton. "The Myth of Superman." Diacritics 2.1 (1972): 14-22. JSTOR. Nov. 2006. Web. 16 Nov. 2011. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/464920>.

- Booker, M. Keith. Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels. Vol. 1 and 2. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2010. Print.

- Bongco, Mila. Reading Comics: Language, Culture, and the Concept of the Superhero in Comic Books. New York: Garland Pub., 2000. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment